Down the Rabbit Hole

Personal Context and Series Origin

Growing up and living in Havana, Cuba, my early reality was often shaped by contradictory rules and distorted versions of truth. Narratives rarely aligned with lived experience, and logic was frequently replaced by improvisation, contradiction, and quiet absurdity. It was within this environment that my relationship to reality became instinctively symbolic rather than literal. As a result, my art began to take on a surreal quality early on, using metaphor and visual symbolism as a way to communicate what could not be stated directly.

My Down the Rabbit Hole series originates from a lifelong relationship with Alice in Wonderland, first through the Disney animated film and later through a deeper engagement with Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass. What initially appeared to me as a whimsical and colorful children’s story gradually revealed itself as something far more enduring, a universe where nonsensical logic conceals sharp observations about power, authority, identity, and growth.

Like much traditional folklore, Wonderland operates on two levels. On the surface, it is playful, absurd, and visually charming. Beneath that surface,

Beauty, Illusion, and Meaning

A recurring theme across the series is the tension between appearance and reality. Just as Wonderland warns against judging by surface logic, these works resist being understood solely through their visual content. Beauty appears frequently, but it is never presented as a simple reward or as truth itself. Instead, beauty is transient, powerful, vulnerable, and often misunderstood, much like the experiences that inspired the work.

Terrace Party

however, it grapples with unmistakably adult themes such as disorientation, arbitrary rules, rigid hierarchies, punishment without reason, and the instability of identity within systems that make little sense. That duality stayed with me throughout my life and became the foundation for this body of work.

In my reinterpretation, Wonderland is not simply fantasy. It is a psychological landscape. Characters, environments, and scenarios are not meant to be read literally, but symbolically. Nothing in these paintings is intended to be understood at face value. What appears playful, indulgent, or decorative often reflects very personal experiences of navigating contradiction, authority, desire, retreat, responsibility and shame.

These works are not autobiographical in a literal sense. Instead, they serve as a process, my way of making sense of experiences that were often confusing, contradictory, or unresolved. By blending Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass into a single visual universe, the series reflects how chaos and order, fantasy and structure, innocence and accountability coexist rather than replace one another.

Terrace Party reimagines the world of Alice in Wonderland not as a children’s fantasy, but as a psychologically charged, adult universe, one shaped by power, absurdity, and survival through imagination. The painting presents a private moment rarely afforded in Wonderland: a pause. Here, the King of Hearts is no longer trapped beneath the Queen’s tyranny or the rigid logic of the court. Instead, he inhabits a hidden terrace, a secret garden above the rules, where pleasure, irony, and observation replace punishment and fear.

On the terrace, authority has stepped aside. The King does not overthrow power; he withdraws from it. His peace is not heroic conquest but strategic disengagement. This reflects a central psychological theme of the work: when systems become arbitrary or cruel, survival may come not from domination, but from creating parallel worlds where one’s inner life remains untouched.

The white roses, so hated by the Queen in the original tale, are reclaimed here as symbols of pre-conflict innocence. They represent beauty before it is conscripted into obedience, before it must be painted red to satisfy authority. Their presence is defiant not through aggression, but through refusal. They exist untouched, uncorrected, and therefore dangerous to a regime built on control.

Inspired by the talking flowers of Wonderland, these figures mature the original concept into something more ambiguous and unsettling. Flowers have long symbolized beauty and innocence, but also impermanence. In this work, they suggest that beauty carries power precisely because it is fleeting.

Their nudity is not erotic provocation but naturalism: unclothed because they have nothing to hide, nothing to perform. They exist in a pre-verbal state, before shame and social consequence.

Above it all, threading through the clouds, runs a bright red roller coaster, a modern transport system for Wonderland. To me, it symbolizes controlled chaos: speed, thrill, and danger engineered into safety. In this sky-bound machine, fantasy is no longer random; it is designed.

Taken together, Terrace Party explores themes of withdrawal versus confrontation, beauty versus authority, innocence versus survival. The work does not deny conflict; it sidesteps it, revealing both the relief and the cost of such a choice. The terrace is peaceful, but it is also isolated. Nothing here can truly harm the King, but nothing here can truly challenge him either.

Ultimately, the painting stands as a meditation on refuge: the secret worlds people build when reality proves unjust. It asks whether peace found through disengagement is a form of freedom, or merely another adaptation. Like Wonderland itself, the answer remains unstable, hovering somewhere between fantasy and truth, play and protection.

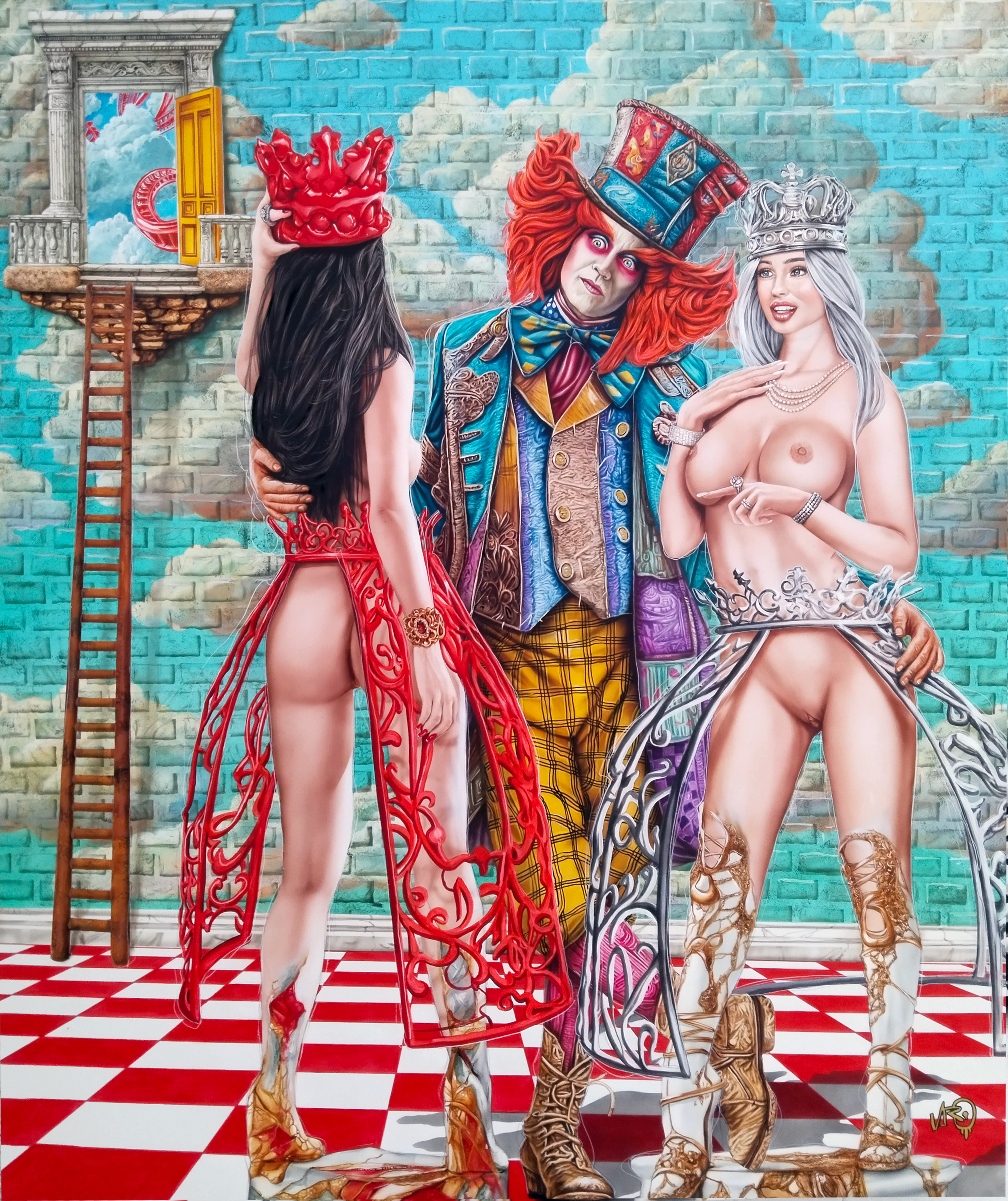

Red, White & Mad

Red, White and Mad imagines a rupture between two neighboring but fundamentally incompatible worlds: Wonderland, governed by emotional absurdity and narrative chaos, and Through the Looking Glass, ruled by logic, hierarchy, and mechanical order. The painting asks the question, what happens when a figure who thrives on madness and fluid identity escapes Wonderland and enters a system that demands structure?

At the center stands the Mad Hatter, no longer merely eccentric but visibly destabilized. Removed from Wonderland’s permissive irrationality, his madness is no longer playful, it becomes exposed. His posture, expression, and costume suggest someone out of phase with the environment: too organic for a mechanical world, too theatrical for a system that reduces beings to pieces on a board. He is neither ruler nor pawn, but an anomaly.

Behind him floats the portal he entered from, a suspended platform with an open doorway leading back into my familiar Wonderland sky, bright clouds, looping red roller coasters, and endless motion. A ladder descends from this portal down into the rigid chessboard floor of the Looking Glass world. This ladder functions as a visual and psychological axis: a one-way escape route from fantasy into structure. Ascension here is not enlightenment but translation, moving from instinct to rule, from impulse to consequence.

Flanking the Hatter are the Red Queen and the White Queen, embodiments of power shaped by the logic of the chessboard. Their bodies begin as human but terminate in stone-like slabs, merging them physically with the game itself. They are no longer autonomous figures; they are living chess pieces, their movement and authority defined by predetermined rules. Power in this universe is not emotional, it’s positional.

The contrast between the queens is deliberate. The White Queen’s crystal crown suggests rigidity, purity, and fragility, an authority built on clarity and reflection, but vulnerable to fracture. The Red Queen’s inflatable crown, by contrast, mocks the idea of permanence. It simulates power rather than embodying it, retaining the absurdity of Wonderland even while operating inside a stricter system. Together, they represent two modes of control: one brittle and absolute, the other performative and inflated.

Psychologically, Red, White and Mad explores what happens when identity formed in chaos is forced into structure. Madness, once adaptive, becomes destabilizing. Power, once theatrical, becomes institutional. The painting does not romanticize either world. Wonderland offers freedom without safety; the Looking Glass offers order without mercy.

The work ultimately positions the Mad Hatter, and by extension the viewer, at an uncomfortable crossroads. Is freedom worth instability? Is order worth dehumanization? The open doorway in the background never closes, but neither does it resolve the tension. It remains suspended, like the painting itself, between escape and entrapment.

Red, White and Mad is not a collision for spectacle’s sake. It is a meditation on systems, identity, and the cost of crossing between them, a surreal allegory about what is lost, and what is exposed, when madness is no longer protected by fantasy and must answer to rules.

The Three Alices

Three Alices reimagines Alice in Wonderland as an internal landscape rather than a fantastical place. Instead of following Alice through a sequence of external adventures, the work presents her as three simultaneous manifestations, three ways of surviving, adapting, and navigating a world governed by illogical rules and shifting power.

Each Alice is the same figure, repeated and transformed, representing different responses to the instability that defines Wonderland. Together, they form a psychological triptych: growth, endurance, and escape

The first Alice wears a towering slice of cake in place of her hair. In the original story, cake causes Alice to grow larger; here it symbolizes forced expansion, being made “bigger” than one is ready for. This Alice embodies pressure, expectation, and accelerated maturity. Growth is not celebratory but imposed, a response to an environment that rewards size, visibility, and performance over comfort or readiness.

The second Alice bears a teapot, referencing Wonderland’s endless tea rituals. In this context, the teapot represents containment and endurance. Tea in Wonderland is ceremonial but nonsensical, rules are followed without purpose, and participation is compulsory. This Alice survives by holding herself together, regulating emotion, and complying outwardly with absurd demands. She is the version that learns to function politely within irrational systems.

The third Alice holds a key, the most explicit symbol of agency and foresight. Keys in Wonderland promise escape but rarely deliver it easily. Doors are the wrong size, timing is always off, and access is perpetually delayed. This Alice represents strategy rather than rebellion, the part of the self that anticipates collapse and prepares exits quietly, valuing leverage over confrontation.

Behind them stretches a wall of roses, lush, beautiful, and suffocating. Traditionally symbols of romance and elegance, the roses here form a barrier rather than a reward. They conceal a small doorway, reminding the viewer that beauty can obstruct just as easily as it can invite. This reflects a

recurring theme in my work: environments that appear refined, cultured, or benevolent can still deny access, protection, or fairness.

From the doorway emerges the March Hare, stumbling forward with a precarious teacup. He represents unmanaged chaos, absurdity leaking through systems that pretend to be orderly. His presence suggests that irrationality is never truly contained; it merely reappears at the margins, unaccountable and unresolved.

The nudity of the figures is not intended as provocation but as vulnerability. Alice, in this universe, is never armored. She navigates Wonderland without protection, adapting internally because external systems do not intervene on her behalf. Exposure becomes a condition of survival.

The Three Alices reflects a mind shaped by inconsistency, where identity fragments not out of weakness, but out of necessity. Rather than a single, stable self, the work presents identity as situational: expand when required, contain when necessary, escape when possible. None of the Alices is “truer” than the others. Each is functional, and each is incomplete on her own.

Wonderland Universe

I have always loved the Adventures of Alice in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass. CS Lewis had the incredible ability to blend fantasy and absurdity with very real world problems and the struggles of growing up. I fell in love with the characters of his universe and the bizarre logic that governed Neverland. I was always captivated by the talking flowers in his stories and imaged them as andromorphic flowers with the bodies of beautiful women and heads of flowers. Like humanity, beauty is fleeting and what better way to capture the beauty and fragility of youth than depicting beautiful women as carefree flowers frolicking in a magical universe. Just like the animal kingdom, animals are born ignorant of their inherent beauty and life totally free from self awareness, bodily shame and just exist as nature intended. I believe this is how talking flowers would exist in Wonderland, free of clothes unaware of their own beauty and in innocent sensuality

Wonderland Re-Imagined

An Erotic Surrealist Series by Darien Varona

Darien Varona’s Wonderland Universe invites viewers down a different kind of rabbit hole—a seductive, absurd, and tender dreamscape where beauty is worshipped, innocence is fleeting, and fantasy is laced with critique.

Loosely inspired by Alice in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass, the series unfolds across two distinct but connected realms.

Wonderland Universe is both a fantasy and a fable, a visual poem about innocence mistaken for seduction, and the way time inevitably pulls

even the most beautiful things back into the earth. In Varona’s hands, eroticism becomes a mirror, not a motive. This is a world of contrasts: performance and purity, spectacle and stillness, desire and decay. Through it all, Varona blurs the line between the erotic and the innocent, the satirical and the sincere. It's a world where we are invited not just to look, but to reflect on why we look, what we project, and what beauty truly means when it blooms without knowing.

The Court of Hearts

logic collide on checkerboard floors and floral wallpaper. The result is both humorous and haunting, a pageant of eroticism and excess, where fantasy becomes a lens for exploring control, vanity, and romantic mythology.

In this surreal kingdom, Darien Varona reimagines Wonderland’s royal court through the lens of erotic satire and Rococo opulence. Aristocrats are blindfolded by tradition, fish butlers serve champagne to topless courtiers, and queens wear crowns made of hearts and desire. Each character appears suspended between performance and pleasure, trapped in a theatrical ballet of seduction and absurd power.

Visual references to 18th-century fashion, pop culture, and dream logic